Phylum Acanothocephala

Common name: thorny-headed worms

Overview

Acanthocephalans are most easily distinguished by the eversible proboscis at the anterior end of the body. The proboscis is covered by small hooks, giving rise to the name �Acanthocephala� which is derived from the Greek �spiny head�. The size and shape of the proboscis varies greatly between species and can be retracted into the body using both muscles and hydraulics. Although some species can exceed 60cm in body length, most are less than 20cm long. All species of Acanthocephala are obligate parasites of vertebrates. Interestingly, molecular studies suggest that the Acanthocephala are closely related to rotifers rather than the other parasitic worm groups and should perhaps be considered as highly modified members of the Rotifera instead of as a discrete phylum.

Distribution and diversity

Worldwide there are approximately 1100 species of acanthocephalans described from freshwater, terrestrial and marine habitats. In Australia there are at least 70 described species from 16 families. Some species have very localised distributions, such as Pomphorhynchus heronensis which is only found in the Great Barrier Reef, whilst others are more cosmopolitan. The distribution of species is also impacted by the level of host specificity, which can vary greatly.

Life cycle

Acanthocephalans are obligate parasites of vertebrates, including fish, birds, mammals and reptiles. Sexes are separate (dioecious) and copulation must occur for fertilisation. The eggs are then laid by the female inside the digestive system of the vertebrate host. Once the embryos pass through the vertebrate host�s digestive system they become food for various arthropod species. The larval stages of the acanthocephalan develop in the intermediate arthropod hosts, forming a cystacanth (resting stage) until the arthropod is eaten by a vertebrate host, at which time the cystacanth lodges in the digestive tract of the definite host and becomes an adult. The arthropod host can sometimes exhibit modified behaviour when infected that increases the chance of it being eaten, such as moving more slowly than uninfected individuals.

Feeding

Adult acanthocephalans attach to the digestive tract of a vertebrate host with their proboscis, exchanging nutrients, gases and wastes through the body wall of the host. They have no mouth or digestive tract.

Ecology

Acanthocephalans spend their adult life inside of the digestive tract of a vertebrate host. Hosts are known to include both marine and freshwater fish, birds and mammals. Often an individual host may have many parasites attached to the digestive tract, but the actual rate of infection within the population of the vertebrate host tends to be small. Human infections are very rare.

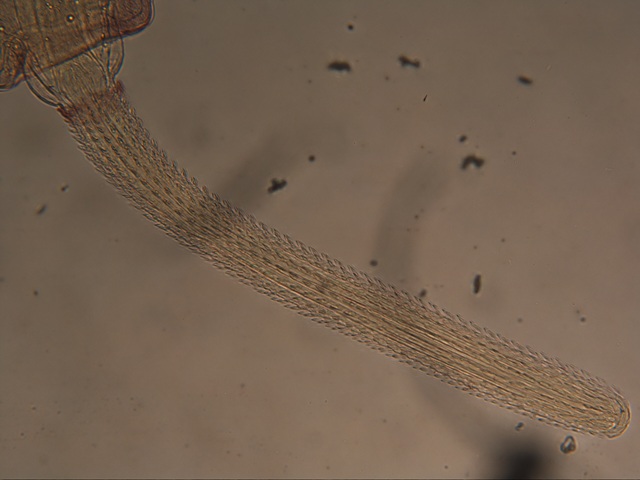

Centrorhynchus sp.

Image � Haylee Weaver, used with permission

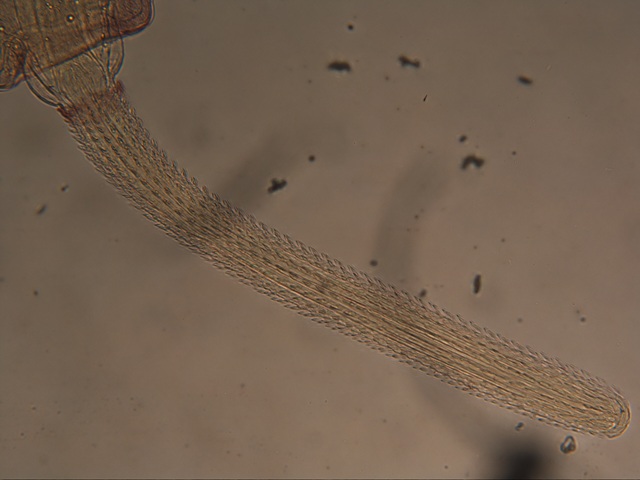

The proboscis of an acanthocephalan

Image � Haylee Weaver, used with permission

References and further information

ABRS Australian Faunal Directory: Acanthocephala

Acantho-What?

Atlas of Living Australia: Acanthocephala

Encyclopedia of Life: Acanthocephala

Tree of Life: Acanthocephala

Fontaneto and Jondelius (2011) Broad taxonomic sampling of mitochondrial cytochrome c oxidase subunit I does not solve the relationships between Rotifera and Acanthocephala. Zoologischer Anzeiger 250, 80-85.

Garcia-Varela et al. (2000) Phylogenetic relationships of Acanthocephala based on analysis of 18S ribosomal RNA gene sequences. Journal of Molecular Evolution 50, 532-540.

Garcia-Varela et al. (2002) Phylogenetic analysis based on 18S ribosomal RNA gene sequences supports the existence of class Polyacanthocephala (Acanthocephala). Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution 23, 288-292.